STILL LIFE WITH LENIN

A FEW WORDS ABOUT A COLD-BLOODED GENIUS WHO LIKED CHILDREN AND CATS

Maxim Gorky called Vladimir Lenin “a man who embodied genius more strikingly than all the great men of his day.”

Gorky also called him “a cold-blooded trickster who spared neither the honor nor the lives of the proletariat.” It’s a good guess Gorky said this rather unflattering cold-blooded-trickster bit after Lenin died on January 21, 1924.

Lenin was also quite fond of children and cats.

October 25, 2017, is the 100th birthday of Lenin’s revolution.1

Happy Birthday, Red October!

All kinds of lousy stuff in Russia led to Lenin’s revolution, primarily: a lousy Tsar Nicholas II, a lousy amount of food, a lousy performance by the Russian Army in WWI that would cost over 2,000,0000 of its soldiers their lives, lousy wages, and lousy living and working conditions for all but the wealthy. In fact, Russia was so lousy Lenin feared it was too backward to adequately house his revolution. He, obviously, got over this fear. After a series of stops and starts throughout the year and the general all-around chaos that accompanies revolutions, Lenin finally seized power on October 25.

October 1917, for an all-too-brief moment, showed people a new a kind of world: workers’ control of production; an eight-hour work day; peasants’ rights to the land they tilled; equal rights for men and women in work and marriage, including the right to divorce and maternity support; homosexuality no longer a crime; free and universal education, from which, according to Trotsky, “The average human type will rise to the heights of an Aristotle, a Goethe, or a Marx. And above this ridge new peaks will rise.”

It didn’t quite work out that way.

The Russian Civil War got in the way. It was an appallingly nasty civil war (as opposed to all those polite civil wars) that lasted from 1917 to 1922 and saw an estimated 7,000,000 to 12,000,000 casualties, mostly civilians.2

Lenin’s health got in the way. A series of strokes left him confined to a wheelchair, out of sight and unable to speak.

Stalin got in the way. Before he died, Lenin warned fellow Bolsheviks about his eventual successor, Stalin, with the words, “That cook will concoct nothing but peppery dishes.” This is an understatement from a man not naturally inclined toward understatement.3 Lenin went so far as to ask for Stalin’s removal as General Secretary of the Central Committee in his will.

Lenin’s dying wishes were ignored; the new world turned to dust and the rest is Stalinism’s ugly history.

Recent history hasn’t treated Lenin so well either,4 specifically his likeness in all sizes of stone, cement, bronze, quartzite, etc. Since the Soviet Union’s collapse on December 26, 1991, a lot of Lenin statues have come tumbling down all over the former empire and its satellites.

Take Ukraine, for example. 5,500 Lenin statues populated Ukraine before the Soviet Union’s fateful 1991 day. 5,500 Lenin statues is a lot of Lenin statues.5 By the end of 2015, there were only 1,320 Lenin statues left in Ukraine. 1,320 Lenin statues is still a lot of Lenin statues but nowhere near 5,500 Lenin statues.

Ukraine even had a name for the removal of Lenin statues: Leninfall. It also had a website to track the downfall of Lenin statues called Reigning Lenins. February 2014 was a particularly rough month for Lenin statues in Kiev; 376 Lenin statues met their demise.

(Roads named after Lenin didn’t fare much better; some had their names changed to Lennon, in honor of John.)

Lenin statues met their fate by way of polite removal and impolite toppling. Kiev’s official deputy architect offered helpful hints for toppling Lenin statues: 1. Don’t endanger bystanders; 2. Climb the pedestal and lasso the statue, preferably around the neck and pull (although “with enough angry people, you just need your hands”); 3. If it’s a big Lenin, tie the rope to a vehicle equipped with a tow hitch; 4. In rural areas, use a tractor; 5. In rare cases of an exceptionally sticky Lenin, hire an arc welder.

Today, there are no official Lenin statues standing in Ukraine.

Some of the Lenins were destroyed; some ended up in scrap yards; some were decapitated; some were pulverized by mobs with sledgehammers in festive public displays of Whack-a-Lenin; some were stored; some were gathered in parks to begin life anew as playground structures; one was refashioned into a Darth Vader statue; and some made their way (along with statues of other Soviet BFDs) to the underwater “Alley of Leaders” museum at the bottom of the Black Sea.6 (In the spirit of true Marxist/Leninist thought, admission to the museum is free.)

One bronze 16-foot, 8.5-ton Lenin monument trekked from a Poprad, Slovakia, junkyard to Seattle, Washington.7 Lots of Seattleites like their Lenin statue, saying things like, “Beautiful and incredibly well-sculpted statue, an important piece of the world’s history. Good coffee too. Five stars.” Lots of Seattleites don’t like their Lenin statue, saying things like, “Imagine a statue in Westlake Plaza of Hitler…Unthinkable…Yet, under the insidious, value-neutral rubric of ‘provocative art,’ Seattle proudly displays a larger-than-life sculpture of a man equally abhorrent.”

Some Lenin statues, albeit smaller than Seattle’s Lenin statue, made it into this series, called Still Life with Lenin.

The Tate Museum defines “still life” this way: “The subject matter of a still life is anything that does not move or is dead [e.g., Lenin, Leninism, Lenin’s revolution, Lenin’s reputation, Lenin statues, roads named after Lenin, cities named after Lenin, etc.]. Still life includes all kinds of man-made or natural objects, cut flowers, fruit, vegetables, fish, game, wine, and so on [e.g., borscht, packaged and canned Russian food, commemorative Seattle World’s Fair plates, Leninade soda, one goldfish, toy cranes, porcelain cats, etc.]. Still life can be a celebration of material pleasures, such as food and wine, or often a warning of the ephemerality of these pleasures and of the brevity of human life (see memento mori).”8

Long live long-dead Lenin statues resurrected in Still Life with Lenin art!

If you’re living your days according to the Julian calendar, the revolution’s birthday is November 5.

Lenin was a nasty civil warrior—unless you consider murdering the deposed Tsar Nicholas II and his family in a cellar and creating the Extraordinary Commission for Combating Counterrevolution and Sabotage (mercifully shorted to Cheka in Russian), a particularly nasty secret police secretly dispensing “revolutionary justice” to perceived enemies not nasty. Lenin called the Cheka the revolution’s “sword and shield” and named the nasty Feliks Dzerzhinsky its boss. Dzerzhinsky was very clear about his job: “I do not seek forms of justice. We are not in need of justice. It is war now—face to face, a fight to the finish. Life or Death.” The latter usually ruled the Cheka’s day.

A man who said, “The Capitalists will sell us the rope with which we will hang them,” is a man not predisposed to understatement.

Even Vladimir Putin doesn’t much care for his fellow Vladimir, accusing Lenin of planting “an atomic bomb under the building that is called Russia and which would later explode.” But, then again, Putin doesn’t much care for anybody not named Vladimir Putin, much less the idea of glorifying the overthrow of any autocratic ruler (e.g., Vladimir Putin), and per Putin’s wishes, there will be no official celebration of the centenary birthday of Lenin’s revolution in Putin’s Russia.

Ukraine, with its 5,500 Lenin statues, was a real Lenin-statue show-off; the rest of the big-assed Soviet Union had 7,000 Lenin statues.

Cape Tarkhankut, Crimea, 45.333935/32.569803, to be exact.

3526 Fremont Pl, Seattle, WA 98103, 47.651355/-122.350965, to be exact.

Latin: “Remember that you have to die.” This reminder apparently now applies to Lenin statues.

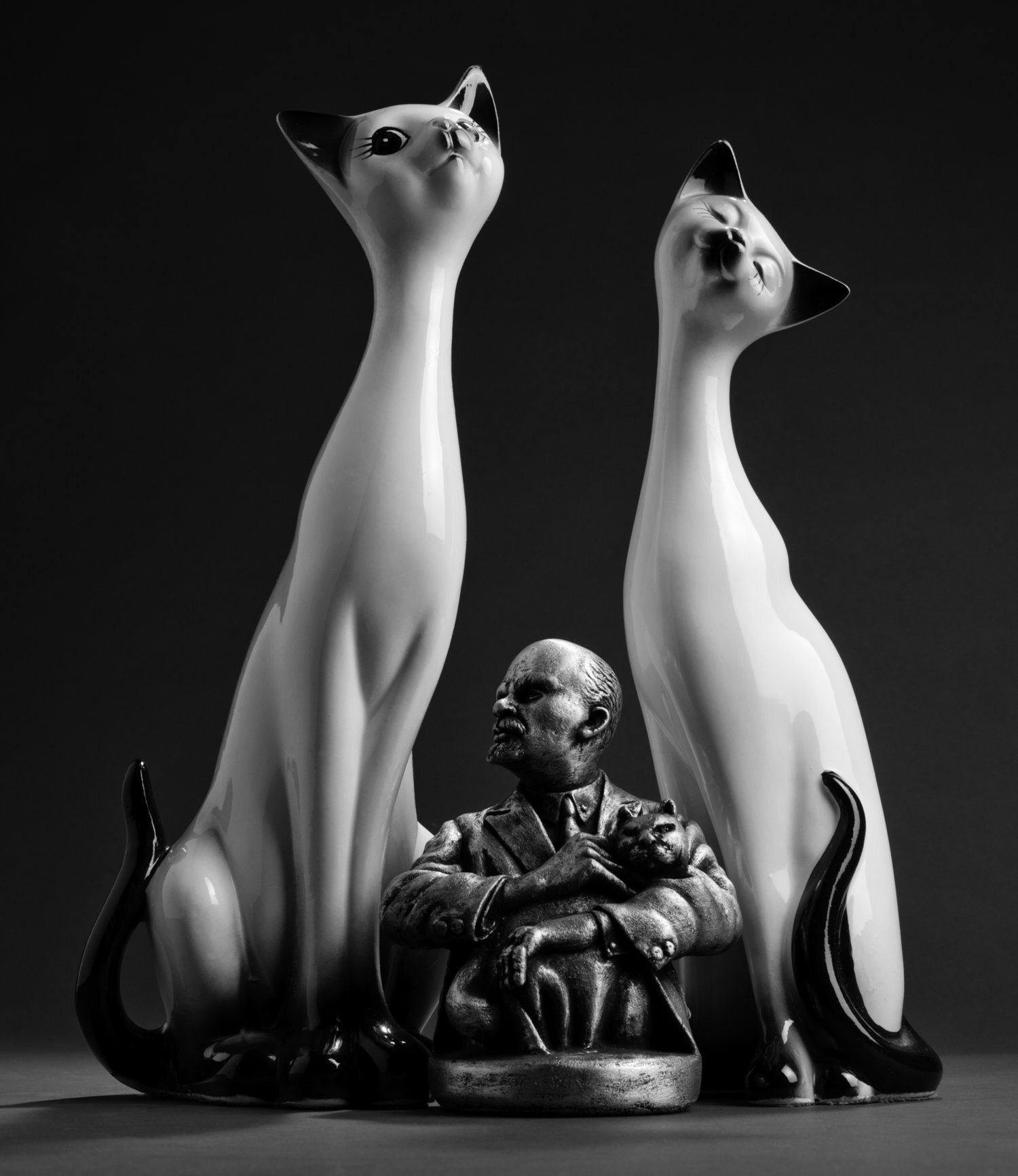

Still Life with Lenin and Three Cats

2017

Digital Print on Hahnemuhle Photo Pearl

10 x 11.5 inches

Edition of 10

Still Life with Lenin and Dead Roses

2017

Digital Print on Hahnemuhle Photo Pearl

10 x 15 inches

Edition of 10

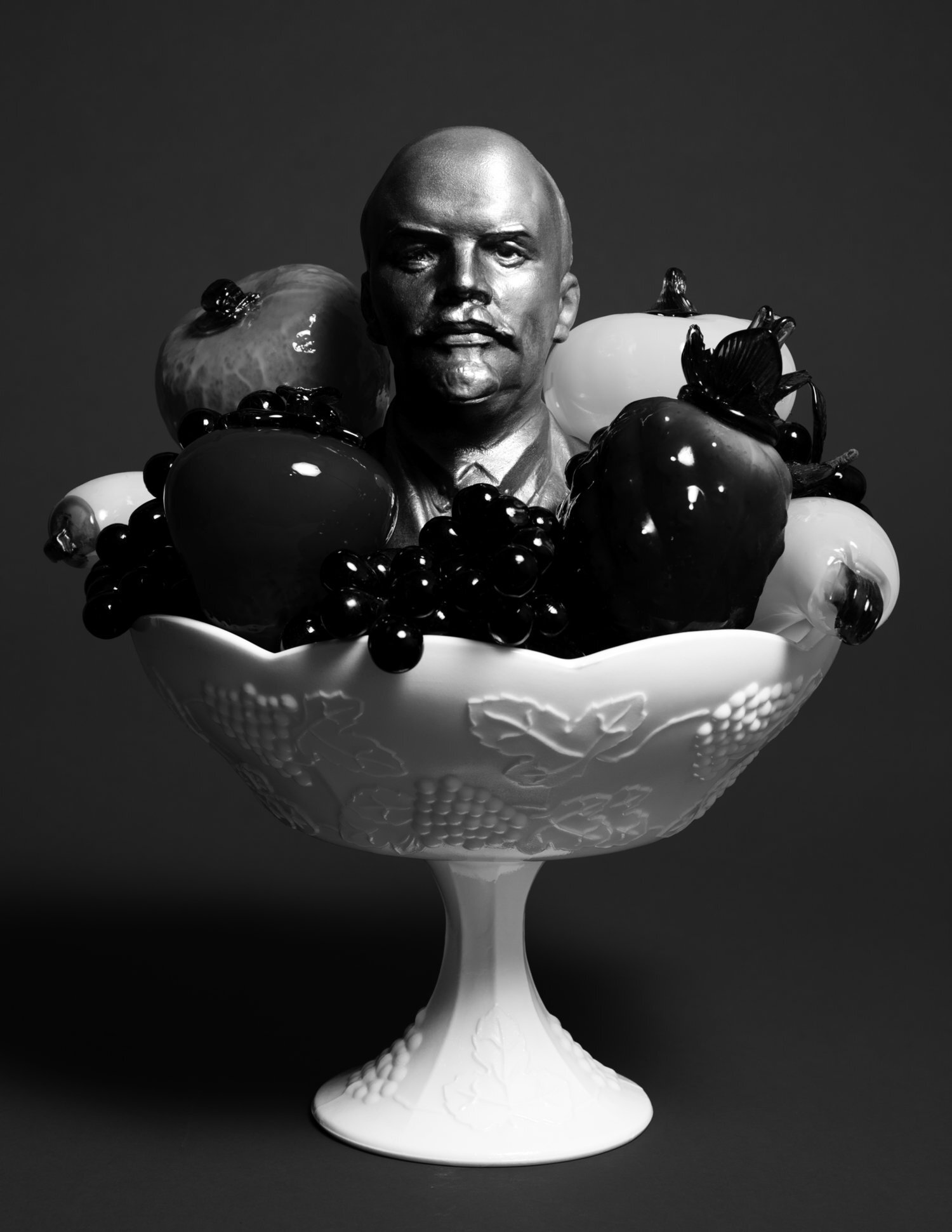

Still Life with Lenin and a Bowl of Fruit

2017

Digital Print on Hahnemuhle Photo Pearl

10 x 13 inches

Edition of 10

Still Life with Lenin and Collected Works of Lenin, Vol. 1-15

2017

Digital Print on Hahnemuhle Photo Pearl

10 x 11.75 inches

Edition of 10

Still Life with Lenin in Borscht

2017

Digital Print on Hahnemuhle Photo Pearl

10 x 15 inches

Edition of 10

Still Life with Lenin and Smoked Mackerel

2017

Digital Print on Hahnemuhle Photo Pearl

10 x 13.5 inches

Edition of 10

Still Life with St. Lenin in Seattle, WA.

2017

Digital Print on Hahnemuhle Photo Pearl

10 x 12.5 inches

Edition of 10

Still Life with Lenin and Russian Groceries

2017

Digital Print on Hahnemuhle Photo Pearl

10 x 15 inches

Edition of 10

Still Life with Lenin and Leninade

2017

Digital Print on Hahnemuhle Photo Pearl

10 x 10.75 inches

Edition of 10

Still Life with Lenin and Hitler Saved My Life and Other Books

2017

Digital Print on Hahnemuhle Photo Pearl

10 x 15 inches

Edition of 10

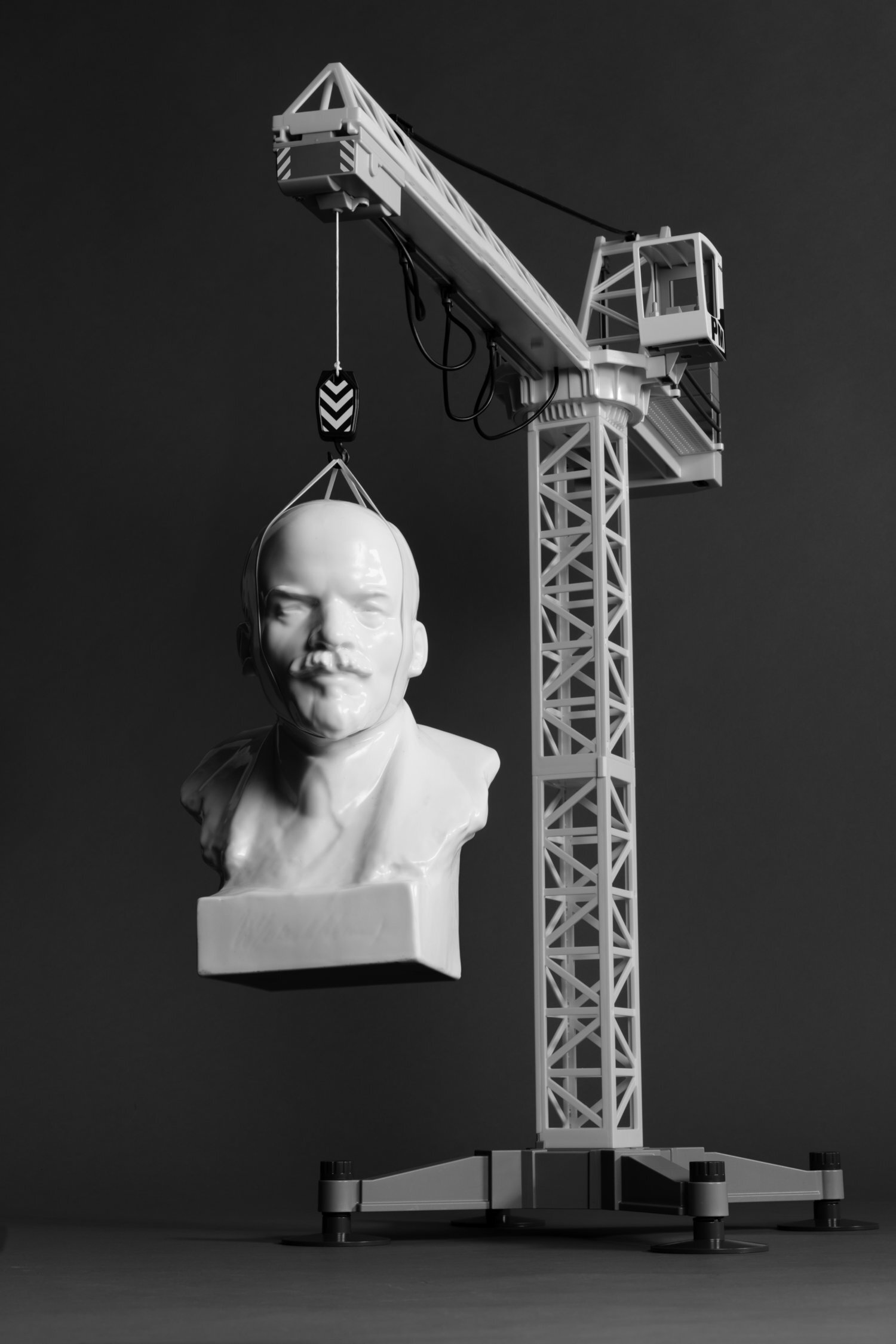

Still Life with Lenin and a Ukrainian Crane

2017

Digital Print on Hahnemuhle Photo Pearl

5 x 7.5 inches

Edition of 10

Still Life with Lenin and One Goldfish

2017

Digital Print on Hahnemuhle Photo Pearl

10 x 10 inches

Edition of 10

Still Life with Lenin and Kholodet

2017

Digital Print on Hahnemuhle Photo Pearl

10 x 13 inches

Edition of 10

Happy Birthday, Russian Revolution!

2017

Pulverized polyurethane, brushed aluminum, chrome-based paint

45 x 24 x 22.75